History

In December 1654, Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, sent an invading force to sack the city of Santo Domingo, Hispaniola. The raiding forces, led by Admiral Penn and General Venables, landed on the shores of Hispaniola, 50 kilometers from the intended target. Already short on supplies and water, they started the long and arduous over-land slog to reach the city. The journey was slow and taxing, and the men, now tired, thirsty and hungry, foraged for food or water as they made progress, but the water they found was polluted making many of them sick. By the time they reached the Spanish forces, many were in no shape to fight and many were mutinous.

The battle for the city was one that was destined to fail. The tired, sick and hungry army under General Venables, were no match for the Spanish. They began a retreat to the landing site, with the Spanish in pursuit. They were only spared from a complete massacre when a landing party from the ships came ashore to provide cover for their retreat. At the end of the battle, a third of the group was missing or dead, and the remaining two-thirds were tired and morally dejected, weakened by fatigue, wounds or by illness.

Fearing Cromwell's response to their failure at Santo Domingo, the leadership decided to attack another Spanish holding that was known to be much weaker in defenses: Jamaica. The Spanish settlers in Jamaica at the time are estimated to have been around 2,500, and the surviving English forces of the failed attempt to capture Hispaniola, at around 8,000.

The English arrived off Kingston Harbor on May 10th, 1655. They sailed a boat in advance to Passage Fort, which gave covering fire for smaller vessels carrying the invading land forces. The resistance was minimal, and no one was hurt during the landing. The Spanish defenders had abandoned their positions on seeing the armada of ships and soldiers coming ashore. The English advanced on the Spanish capital of the island, located 6 miles (9.66km) away; St. Jago de la Vega (now named Spanish Town). On their way, they encountered a Spaniard bearing a flag of truce and gifts. Commander Venables, still weary from their unsuccessful campaign in Hispaniola and wishing to avoid unnecessary bloodshed, offered the Spanish governor the terms of surrender.

The Spanish surrendered and the majority of the Spanish left, but the fight to keep the island continued for another five years. A group of Spaniards, with the aid of the Maroons on the island, presented a strong resistance and it wasn't until 1660 that the Spanish were finally pushed from the island.

The Birth of Port Royal

The importance of naval supremacy was quickly identified as being of key importance to the success and security of Jamaica, which was, at that time, little more than a military outpost. There was an ongoing push by Britain, for settlers, but that was slow in coming. Kingston Harbor was rapidly expanded, and within weeks, the construction of Fort Cromwell was started at the tip of the Palisadoes peninsula. The fort was later renamed to Fort Charles. A small community of merchants, mariners, craftsmen and prostitutes built up around the fort and the area became known as Point Cagway, later renamed to Port Royal.

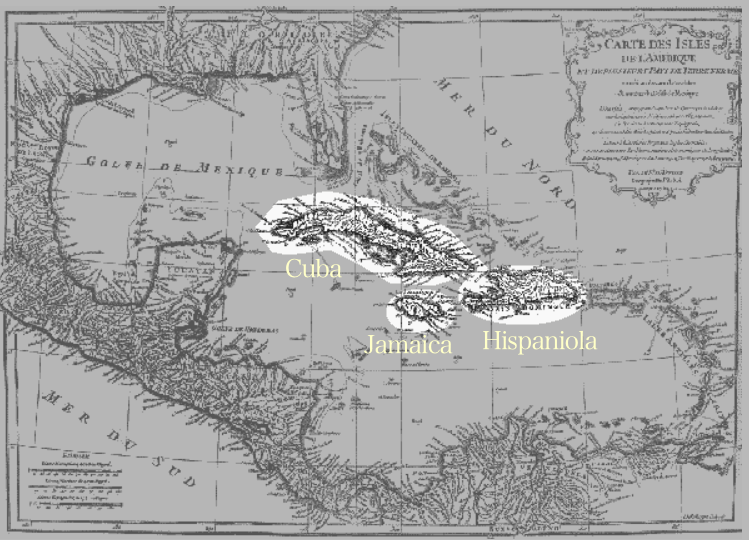

The location of Port Royal on the tip of the narrow peninsular of the Palisadoes, which projects like a finger encircling the Kingston harbor, made it a perfect place to control access to the harbor, and to defend Kingston and Spanish Town from naval attacks. Edward D'Oyley, one of the officers who led the invasion, realized that the strategic placement of this spit of land, as well as the location of the island in the midst of Spanish colonies of Cuba and Hispaniola, made it an ideal place to harass Spanish settlements and shipping lanes in the Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean. He saw the potential for a deal with the buccaneers, so he made an offer for them to establish a base as a safe haven in Port Royal. He knew their presence would provide the deterrent he needed to keep invading forces away.

Recognizing the strategic and proximity of the city close to Spanish shipping lanes and neighboring Spanish settlements, the buccaneers accepted the deal. The city soon became a major port for trade and shipping, and one of the most popular ports of call for thieves, prostitutes, pirates and state-sanctioned privateers.

Port Royal Fort circa 1690

Painting courtesy of Peter Dunn, Archaeological Reconstruction Artist

Although Port Royal was designed to serve as a defensive fortification guarding the entrance to the harbor, it assumed much greater importance. Its well-positioned location within a well-protected harbor and its flat topography surrounded by deep water close to shore, made it an ideal place for loading, unloading and servicing of large ships. Ships' captains, merchants, and craftsmen established themselves in Port Royal to take advantage of the trading and outfitting opportunities. As Jamaica's economy grew and changed between 1655 and 1692, Port Royal grew faster than any town founded by the English in the New World, and it became the most economically important English port in the Americas.

Coinciding with the city's early development between 1660 and 1671, officially sanctioned privateering was a common practice, and nearly half of the 4000 inhabitants were involved in this trade in 1689. The buccaneer era greatly enriched the port, but it was to be a short-lived and colorful period. In the terms of the 1670 Treaty of Madrid that England signed, Spain ceded ownership of Jamaica to England, and England agreed to the cessation of privateering. The practice, however, continued in one form or another into the 18th century. Indeed, it was the Spanish money flowing into the coffers of Port Royal, through trade and plunder, that made the port so economically visible.After 1670, the importance of Port Royal and Jamaica to England increased due to its trade in slaves, sugar, and raw materials. It became the mercantile center of the Caribbean, part of an expansive trade network, with vast amounts of goods flowing in and out of its harbor. That trading included trading and/or looting of coastal Spanish towns throughout Spanish America. It was a wealthy city of merchants, artisans, ships' captains, slaves, and, of course, notorious pirates, who gave it its "wickedest city in the world" reputation. It is said that one out of every four buildings was either a bar or a place of prostitution.

Port Royal circa 1690

Painting courtesy of Peter Dunn, Archaeological Reconstruction Artist

Only Boston, Massachusetts, rivaled Port Royal in size and importance. In 1690, Boston had a population of approximately 6,000, while population estimates for Port Royal in 1692 range from 6,500 to 10,000. Many of the city's 2,000 buildings, densely packed into 51 acres, were made of brick (a sign of wealth). Some were four stories tall. In 1688, 213 ships visited Port Royal, while 226 ships made port in all of New England. The probate inventories of many of Port Royal inhabitants (distributed between the Jamaica Public Archives and the Island Record Office in Spanish Town), reveal a high degree of prosperity, and that unlike the other English colonies, Jamaica used coins for currency instead of commodity exchange.

In short, Port Royal was the most successful entrepot in the 17th-century English New World. Its social structure was quite different from either that of New England or of the tobacco-driven economy of Maryland and Virginia. Port Royal had a tolerant, laissez-faire attitude that allowed for a diversity of religious expression and lifestyles. There is early mention of merchants, who were Quakers, Papists, Puritans, Presbyterians, Jews, and Anglicans, practicing their religion openly alongside the freewheeling sailors and pirates who frequented the port.

Source: Texas A&M Nautical Archaeology

Museums and Historical Places

Fort Charles is at the western tip of The Palisadoes and is very well-preserved with its rows of semicircular gun ports in the fading red brickwork. The young lieutenant Nelson was stationed here, and a plaque in his memory reads: "You who tread in his footprints, remember his glory."

Fort Charles Maritime Museum exhibits displays of man's relationship to the sea from the times of the Arawaks, and traces the development of Jamaican maritime history. There is a scaled model of the fort and models of ships of past eras. It is located in the old British naval headquarters and is open from 10 am to 4 pm daily.

The National Museum of Historical Archaeology is located in what used to be the naval hospital that spent a lot of its time fighting epidemics of yellow fever. The museum displays the history of the Jamaican people and techniques of excavation being used in the study of Port Royal's history based on marine and land deposits. It is open from 10 am to 5 pm, Monday to Saturday.

Giddy House, close to the fort, is a former artillery store, and gets its name because of its strange tilt, resulting from the 1907 earthquake.

Port Royal Marine Laboratory of the University of the West Indies is based in Port Royal. Founded in 1955, the laboratory began as a small room in the Old Naval Dockyard but later moved to a one-acre site, "Crab Hall' beside the navy Hospital.

The Port Royal Laboratory has been important in undergraduate teaching of marine biology and marine ecology and in recent years has undertaken courses in aquaculture, fisheries and coastal management. As you head back along the promontory, you can spot the remains of other fortifications and be on the lookout for wildlife. The whole area is protected and home to a large number of birds, animals and reptiles.